Lady Musgrave Island

I thought for a while about how to adequately describe the experience of this island - but feel I can't, really.

So, I'll skip that part and just show pictures and write about some of really cool and interesting phenomenon that support the island instead.

The Island

First, the island itself. Lady Musgrave Island is a coral cay - a small sandy island on top of a reef.

One current theory says that the Great Barrier Reef formed around what were once hills on the Australian continental plain. As the last ice age drew to a conclusion around 11,700 years ago, sea levels rose approximately 60 meters as the glaciers melted.

Coral reefs started to form around hills on the Australian plains, which became islands as the rising water covered the plains. Gradually, the islands started to erode over time, until nothing remained above the surface - but the reef remained, and flourished. This provided a natural barrier to ocean swells, and over time as all manner of sea creatures lived and expired, the island formed out of the shells, coral, bone and ocean sediment (such as sand) that remained.

The coral base meant there were few nutrients that would be found on continental shelves - and is incompatible with most continental trees and plants as a result. Instead, a very specific variety of tree called Pisonia grandis has evolved pretty much exclusively for these coral-based islands.

The trees are crazy - their unique lack of nutrition means that, though they look like trees, they have very weak wood. Twigs and sticks that fall are more like leaves than wood. These particular trees spread using the native bird population which was vast - tree seeds are sticky to grab on to birds as they fly from island to island, helping ensure propagation of the trees.

The trees still support a colossal population of birds - and oh, man were there birds. Birds everywhere. Birds above, below (the island supports a population of shearwaters that actually bury up to a meter down), aggressive seagulls and a very distinct smell of bird droppings in the forest.

Clams

It's the Great Barrier Reef. I know. Home to nearly 1500 different species of colourful fish and coral and anemonae and cetaceans and sharks and what have you.

The molluscs remained my favorites.

Most of these clams appear to belong to either Tridanca gigas or Tridanca derasa. The largest specimen ever found of T. gigas was 1.3 meters long and weighed nearly 250 kilograms! (imperial 4 ft 6 in/550 lbs)

The colorful striations and dots on each clam are light receptors - if you make a shadow over one, it'll close up as an anti-predatory response.

I can't get enough of the patterns made with these receptors, and the ridiculous variety of colors. I wonder what genetic algorithm determines which clam has which colors? Would a blue-and-black clam's offspring also be blue-and-black?

I was curious how clams got their energy - stationary creatures like it would have a hard time catching anything or consuming local plants, so did some reading.

There are two sources of nutrients for giant clams - filter feeding, and symbiotic algae. Filter feeding means the clam will passively consume nutrients and tiny creatures that float through the sea (such as phytoplankton) - which is more robust of a method for nutrient collection than you might suspect (baleen whales are filter feeders).

Now. Symbiotic algae. It turns out, clams exist in symbiosis with the zooxanthellae dinoflagellate algae. During daytime, the clam will "pucker" it's lips - extending it's internal tissue out - which is covered by zooxanthellae. This puckering will expose the algae to sunlight - which then grows & reproduces through photosynthesis - and then the clam will digest the grown algae, leading to the clam getting its nutrients from the algae and being able to grow.

The only basic requirements for this process is exposure to a lot of sunlight & ocean water, and the clam can then grow nearly endlessly in its solid shell. It's an incredibly robust and simple method of sustenance and utterly fascinating.

Here's one of the clams with it's mantle tissue puckered out.

Zooxanthelle algae is, interestingly enough, also the same algae that feeds corals. It's perhaps one of the most important marine symbiotic species in the world - from the Wikipedia article,

During the day, they provide their host with the organic carbon products of photosynthesis, sometimes providing up to 90% of their host's energy needs for metabolism, growth and reproduction. In return, they receive nutrients, carbon dioxide, and an elevated position with access to sunshine.

Also - regarding clam reproduction, apparently clams are sexual hermaphrodites, which means they produce both eggs and sperm (and can't therefore be quantified as male or female, but are natural they/thems). They can't reproduce on their own, but can interact with any other members of their species - allowing a huge diversity in profligation.

Clams are fascinating.

Coral

Reefs are made, mostly, of coral.

Coral also tends to derive its nutrients from zooxanthellae algae, which live within the coral tissues. This algae is what generally gives coral its color - so generally if you see a colorful coral, you see a healthy coral. Instead of directly consuming the algae, as clams do, coral will try to make its zooxanthellae as happy (and alive) as possible - coral produces $CO_2$ and fresh $H_2O$ as byproducts of cellular respiration, and then zooxanthellae provide the coral with the nutritional byproducts of photosynthesis (such as glucose, glycerol and amino acids).

Seriously. Zooxanthellae for the win. In keeping with their immensely helpful nature, zooxanthellae are also known by the genus Symbiodinium.

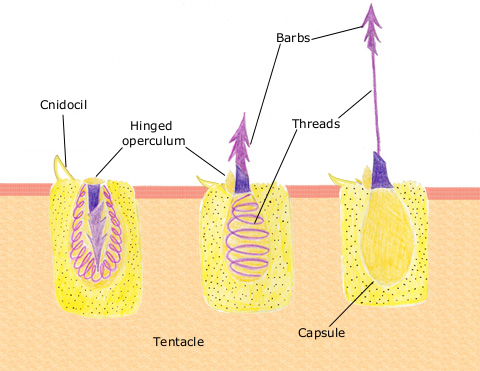

Many varieties of coral are actually semi-carnivorous, too - and will consume zooplankton and some species of small fish, by firing a little poisoned harpoon out of a "stinging cell" called a nematocyst.

On a more sober note, an issue that currently affects most reefs around the world is something called coral bleaching. When the temperature of surroudning waters rise, zooxanthellae will unfortunately start to produce reactive oxygen species (such as hydrogen peroxide ($H_2O_2$), hydroxl radical ($HO$) and nitric oxide ($NO$), to name a few). These reactive species are toxic to the coral, so the coral expels the zooxanthellae - which means that the coral is deprived of a primary source of nutrition and supplementary support. Since Symbiodinium gives color to the coral, bleached coral then turn white when they are expelled. Hence, bleached.

Bleaching doesn't mean the coral are dead, per se - just without a source of nutrients. As water temperatures decrease, zooxanthellae are allowed to move back in to the coral - so it's not an instant-death scenario.

That said, coral bleaching is a primary cause of coral death due to starvation - and, if climate change continues unabated, we might be seeing extensive widespread deaths of entire coral ecosystems within the next few years (in 2005, for instance, approximately half of the reefs in the Caribbean died due to a large coral bleaching event).

Cucumbers

Stichopus chloronotus (green) and (probably) Holothuria leucospilota (red/black).

These shallow sea cucumbers lead a lovely life, consisting of wandering along the shallows and using their feeders to carry organic debris from the seafloor into their mouths. While this does involve a lot of sand consumption, the cucumbers generally have a hardy digestive tract capable of handling copious quantities of not-food.

Weird, cool creatures.

Starfishes

Linckia laevigata (blue) and Nardoa novaecaledoniae (orange).

Both L. laevigata and N. novaecaledoniae have curious feeding habits - they possess an internal cardiac stomach, and will move along the surface of the ocean until they find small fallen sea creatures. Then, they will "expel" their stomach through their mouths onto their prey, digest it, and slowly retract their stomach as the prey becomes small enough to consume. In this way, they are primarily scavengers, however some have been noted to consume algae.

Here's a close-up of the little feet they use to move.

Endlessly fascinating. Could spend a lifetime here and still not have learned but a fraction of what there is to discover.

Sharks

Snorkellers and divers will generally recommend you get out of the water when clouds come out. I was skeptical of this at first - it meant a lot of downtime on cloudy days and felt more like a general sense of "beware" than anything tangible.

So, I was walking on the shore, and clouds covered the sky. The reaction was remarkably quick - 4 sharks within so many minutes.

These are "nurse sharks" (Ginglymostoma cirratum) - etymology unknown - which generally feed on smaller reef fish as well as crustaceans and molluscs. Apparently, nurse sharks are also skilled at suction feeding, and are capable of generating a vacuum force of 0.96 kg/cm$^2$ in bursts - just under atmospheric pressure at sea level (14.96 psi).

Rays

I saw this little guy right after the sharks - within a second he hauled it back to sea so I wasn't able to line up a clear shot.

It looks like it's a blue-spotted fantail ray (Taeniura lymma). These rays generally hunt for molluscs, shrimps and crustaceans by digging through sand, will trap the prey by its broad body and try maneuvering it to its mouth.